- Home

- Tessa de Loo

The Twins Page 3

The Twins Read online

Page 3

‘My Dutch father.’ Lotte smiled uneasily.

‘What was he like? … I mean, what sort of people? … As a child I imagined all kinds of …’ Anna groped in the air with her hands. ‘Because I knew absolutely nothing, I made it up in my own fashion … I dreamed of calling on you … You have no idea how hard it was not to hear anything from you … Everyone behaved as though you didn’t exist … So, anyway, what kind of people were they …?’

Lotte pursed her lips. A dubious attraction emanated from the idea of raking up old memories. They were lying deeply stashed away in a corner of her memory, under a thick layer of dust and cobwebs. Wasn’t it better to let them be than to go poking about there? Yet they were a part of herself; there was something tempting about bringing them to life. In such improbable surroundings as the Thermal Institute, going after them at Anna’s request. Challenged by the absurdity, even the immorality of it she half-closed her eyes and began to murmur softly to herself.

On Saturday evenings he scrubbed his four daughters clean in a wash-tub filled with warm soapsuds, growling ‘Sit still!’ while his wife was taking advantage of late shopping hours. The ritual was rounded off with a glass of warm milk; he whistled as he brought it to the boil. Four nighties, eight naked feet – sipping as slowly as possible to spin out the time. After he had accepted four goodnight kisses he resolutely sent them to bed. In summer the scenario worked differently. Then a group of older girls from the village gathered on the overgrown football pitch in front of the house to do rhythmic gymnastics in the mist rising from the grass. The silhouette of a delivery van was outlined against the red sky, churning up clouds of dust along the sandy path as it approached at speed. It came to a halt at the entrance to the field, the back door was opened, and then the miracle was performed that took Lotte’s breath away every Saturday evening: muscular arms hauled a piano out and placed it in a strategic position in the field amid buttercups and sorrel. Then a young man in an off-white summer suit sat down at the piano and launched classical melodies at marching pace into the evening sky.

The girls from the gymnastics club kicked their legs high and bent far backwards; they stood on their toes with their arms stretched over their heads as though they had landed on the ground all together with invisible parachutes. All to the pianist’s inexorable quadruple time. Mies, Maria, Jet and Lotte, still warm from the bath, observed the spectacle from the edge of the fence until they saw their mother looming up in the distance, erect on her Gazelle bicycle, its handlebars seeming to sag under the weight of bulging shopping bags.

No bath for Anna. Soon after her arrival at the ancestral farm on the Lippe, it turned out that baths were regarded there as an exceptional, generally mistrusted activity. Immediately after the journey her grandfather sank into his usual chair, resting his clog socks on the edge of the cast-iron stove – an acrid smell of mould filled the small cluttered living-room – he was to die without his pale chest ever having been defiled by a piece of soap. ‘I want a bath,’ Anna whined. Mollified by the stubbornness with which the niece stuck to her principles, Aunt Liesl put a large kettle of water on the fire and filled a wash-tub on the flagstone floor. Thus was the tone set for a long-lasting habit, which Anna maintained single-handedly after Aunt Liesl had left the house. Years later, when she began to lock the door for the process, Uncle Heinrich rattled the handle and called with a titillated laugh, ‘You must be absolutely filthy if you have to make such a fuss.’

The village children were thoroughly suspicious of her town manners and cultured accent. They pinned a note to the back of her coat: Go away! She was outstanding at school – her classmates observed her tours de force with a mixture of fear and envy, and shunned her company. She was gradually realizing that to be dead meant that someone would always be absent from now on and could not be brought back, even by your fervent longing that he would make short work of your tormentors with his powerful demeanour. According to this definition Lotte was dead too. Anna kept hammering away about her return, circling around her grandfather until he uttered viciously, ‘Don’t be so impatient! If she doesn’t recover properly she’ll die too. Is that what you want by any chance?’ Desperately she turned to Aunt Liesl, who was spinning and sang in a thin high voice, ‘Ich weiss nicht what’s supposed to happen …’ Her sagging bosom rocked in time to the wheel’s movement. Above her head hung a print that the family had received as a gift during the war when a son had been killed in action. ‘There is no greater love than to lay down your life for your country’ was written in decorative letters beneath a dying soldier and an angel who held out to him the palm of victory. Anna slunk off outside in the vague hope that Uncle Heinrich could shed some light on the question. But he was sitting on the WC in the back garden, in a wooden hut painted dark green, tall and narrow, and lopsided because of an underground branch in the Lippe. The door had a heart shape sawn out of it; it stood wide open. He was sitting sprawled out, involved in conversation with a neighbour, who was engaged in the same activity on the other side of a field of mangel-wurzels, also with the door open. The tête-à-tête concerned the shooting match and girls – Anna did not hazard this rifle range.

She trudged despondently to the river, crossed the bridge and stood with shoulders drooped in front of a shrine to the Virgin, in the shadow of an overhanging elderberry. Someone had put a bunch of dark red peonies at the base of the statue. The mother was looking down devotedly on her child, a mysterious, hidden intimacy suggesting that all curious stares were excluded. Anna had the impulse to upset this introspection and to damage the pious face. Instead of that she tugged the flowers out of the vase, ran on to the bridge with them and threw them into the Lippe with an angry toss of the wrist. She looked at them as they floated slowly away towards Holland. One peony behaved deviantly: after circling wildly in an eddy it was sucked into the depths. Anna stared enviously at the spot where the flower had disappeared. To vanish from one moment to the next, she wanted that for herself too – to join her beloved absent ones. There was a stiff breeze carrying the smell of damp grass and straw. She did not resist as it took hold of her and raised her up, her clothes flapping. It went aloft, in a deafening rustle, straight into the cloudless sky. Far down beneath her she saw her grandfather’s farm, half hidden beneath the crown of a lime tree. She saw the fields, the grassy alluvial sand banks where cattle grazed, the school, the church, the Landolinus chapel – the whole settlement on both sides of the Lippe, which tried to transcend its insignificance through desperate contortions, its inhabitants inflating the village’s status with fabrications about Widukind who, with his Saxon hordes, had offered bloody resistance to the king of the Frankish empire there. Anna, hovering far above it, had nothing to do with it.

Lotte lay in the garden in a pine summerhouse that was set on a rotating axle so that it could be turned towards the sun or away from it as preferred. Stretched out in bed she turned with the weather – her narrow face on a white lace-trimmed pillow. Her Dutch mother drew a kitchen chair up to the bed and taught her Dutch; she also gave her a book of fairy-tales by the Brothers Grimm, with romantic illustrations. In German, ‘So that you don’t forget your mother tongue,’ she said. She herself looked as though she had stepped out of the book of fairy-tales. She was tall, erect and proud; she laughed easily – her teeth were as white as the doves that flew to and fro to the dovecot at the edge of the wood. Everything about her shone: her complexion, her blue eyes, her long brown hair held in place by a few strategically placed tortoiseshell combs. An abundance of the joys of living poured forth over everyone who came within her orbit. But the most fairy-tale thing about her was her unfeminine strength. If she saw her husband lugging a sack of coal she rushed over to him to take the burden lovingly off him – she carried it to the fireplace as though it were a bag of feathers.

Lotte soon realized that she had ended up in a related branch of the family: those of the long noses. The head of the line looked strikingly like her own father. The same acute melancholy gaze, the thin arched nose,

the dark hair combed back with the same moustache. In fact he was a first cousin of her father and had passed his genetic characteristics onto his daughters undiluted; a similar proud and sensitive organ of smell was already developing in them, via the round children’s nose. Years later, when it had become dangerous to have such a long nose in the middle of your face, this simple biological fact would almost cost one of them her life.

Depending on the position of the sun, Lotte was always able to see another part of the universe from her lodge. There was the wood, on the other side of a wide ditch that bordered the garden on two sides. A group of conifers formed a natural gate by the dovecot, a dark niche that drew her gaze to it – across a mossy bridge straight into the twilight between the trees. From another sightline she saw the orchards and kitchen garden where the pumpkins expanded so fast that Lotte thought she could hear them groaning from their growing pains, having become susceptible to fairy-tales in which apples and bread rolls could speak. Then there was the view of the house and a sturdy octagonal crenellated water-tower – all in masonry with decorative arches in green glazed brick over the windows and doors. One day she saw her Dutch father climbing up there to hoist a large flag. Her breath caught when she saw the diminutive figure at the top beside a flag that flapped in the wind like a loose sail – was it not the fate of fathers suddenly to be blown away out of the world?

At night she slept inside the house in a separate room. Then the nighttime landscape unfolded: never-beheld hills and rocks, fir trees and alpine meadows, mountain streams. Her grandfather was hovering above them on the tails of his mourning coat; Anna was hanging from his claws, screaming silently. Lotte dashed over hills, up high, down low, to escape from the shadow he was casting over her. The ground was rolling away beneath her, she was stumbling over cobbles – she woke up screaming and coughing. She was lifted up and put into another bed, where she slept in the crook of her Dutch mother’s arm without further upset.

‘Then why did they rush off with us, like thieves in the night,’ Lotte asked herself, ‘straight after the funeral?’

Anna laughed wrily. ‘Because it was a disaster. With the useful bonus of an extra labourer on the farm. It was a village of conservative, Catholic farmers – that’s what it was like then. Father fled from that milieu when he was nineteen. He went to Cologne and became a socialist. That short-sighted old man had never been able to stomach it, verstehst du. And then, as soon as the son who had defected was dead, he came to rescue us from that hotbed of heathendom and socialism. A hit-and-run operation, to prevent Aunt Käthe keeping us.’

Lotte had a light-headed feeling. It was unbelievable that this grotesque family history concerned her too. All of a sudden, just like that, the wax was being broken on a bitter mystery that she had sealed down an infinitely long time ago: shhh, don’t think about it any more, it never happened.

‘But …’ she objected weakly, ‘why did he … me … let me go to Holland then?’ It seemed as though she was hearing only the echo of her own voice, or someone else was speaking on her behalf.

Leaning forward Anna laid a plump hand on Lotte’s. ‘It didn’t suit him that you were ill. A healthy child was a good investment, but a sick child … Doctors, medicines, a sanatorium, a funeral: that could only cost money. It suited him that his sister Elisabeth offered to take you – although he entirely disapproved of her and was deeply suspicious of her fashionable mourning outfit. Her son, she said, lived not far from Amsterdam in a dry, wooded region, which was therapeutic for TB sufferers; there was even a sanatorium in the district. Na ja, you know all that much better than I do. This aunt herself had escaped from life on the farm in the previous century – imagine it, about a hundred years ago – to go to Holland as a maid servant and to marry there. I heard all that from Aunt Liesl, years after the war. Grandfather never showed the slightest interest in you any more, not even after you were cured. A cat that was sickly in its youth never grew into a healthy strong animal, was his attitude.’

‘I wonder,’ Lotte forced a smile, ‘if he would have let me go if he had known that I had been entrusted to a Stalinist who brought me up on torrents of abuse against the Pope and the Church.’

‘Mein Gott, really?’ Bewildered, Anna shook her head. ‘What an irony … because I would not have survived for long without that same Church.’

Bread and hobnails, sausage and safety-pins, nothing was unthinkable in the richly stocked shop and adjoining café where Anna read out her shopping list in a clear voice. ‘Do you want to earn ten pfennigs, child?’ lisped the woman behind the counter; the missing front tooth did not restrain her from smiling with a grocer’s cunning. Anna nodded. ‘Then come and read to my mother twice a week.’ The mother, blind from cataracts, sat in a back room by the window, crumpled up in a worn-out tub chair. On the table in front of her were the mystical reflections of Catharina van Emmerik. Each session of reading aloud had to close with the old woman’s favourite passage: the one concerning the flagellation of Jesus before the crucifixion. The saint of Emmerik sketched the various stages of the flagellation without reticence: first he was whipped for a while with an ordinary whip, then a new, well-equipped soldier took the former’s place, with a split whip, and as his strength diminished he in turn was replaced by a soldier with a flagellum, the barbs of which penetrated deeply into the skin. At each blow the woman hit the arm of the chair with her bony fingers, her mouth uttered moans that were somewhere between shrieks of pain and encouragement. Anna also reached a climax every time: the fusing together of her compassion for Jesus and her rage at the Roman soldiers and the actual instigators, the Jews. After she had closed the book with trembling fingers, the feeling of indignation slowly ebbed away. ‘Come over here …’ the old woman beckoned. Reluctantly Anna approached her chair. The old fingers that had drummed rhythmically on the armrest just before, groped at her plump limbs. Coolly Anna noted the signs of decay – liver spots on the white face, bags under the pale staring eyes, thin hair where the scalp shone through. ‘Ach, stroke me on my head …’ said the woman softly, squeezing Anna’s hand. Anna did not obey. ‘Bitte, bitte, stroke my head …’ Was this part of the reading aloud, like an encore? Eventually she did what she had been asked, quickly and mechanically. ‘Our Anna prays for money,’ Uncle Heinrich chuckled to everyone who would hear him, ‘till she foams at the mouth.’

Anna did not ignore the flagellation of Jesus, who had gradually been taking the place of her father. Each Sunday she sat between her grandfather and her aunt in the Catholic church that dated back to the mass conversions of the Germanic peoples. Looking round, her eyes had soon discovered a bas-relief depicting the event on one of the whitewashed walls. One day Alois Jacobsmeyer, the pastor, who was reciting his breviary in a side chapel, saw her walking down the aisle with a wooden stool in her hand. Intently, she turned to the right, towards a series of age-old bas-reliefs depicting the crucifixion of Christ. She climbed onto the stool and began to give Jesus’s tormentors a tremendous beating with her fists. ‘So!’ resounded vengefully through the church. ‘So!’ Worried, scratching his head, Jacobsmeyer asked himself whether the relief would be able to withstand such iconoclasm.

3

The get-together was threatening to take on a slightly more caustic character. Lotte had been uncomfortably nettled by the scene in the church as Anna, not without tenderness, described it. Suddenly a razor-sharp, hideous feeling flamed up in her that had lain smouldering all that time.

‘And in that way the Church gave all of you a nice little alibi for murdering six million people,’ she said. Red blotches were appearing on her cheeks.

‘Exactly,’ said Anna, ‘that’s it exactly! That’s why I am telling you, so that you’ll understand that its foundations were already matured when we were young.’

‘I do not believe,’ Lotte slowly rose from her chair, ‘I need to understand. First, all of you people set fire to the world and on top of that you want us to go deeply into your motives.’

‘You people? You are talking about your own people.’

‘I have nothing to do with that people,’ Lotte cried, full of abhorrence. Urging herself to be calm, she permitted herself to continue condescendingly, ‘I am Dutch, in heart and soul.’

Did any compassion seep into the glance Anna cast her? ‘Meine Liebe,’ she said soothingly, ‘for six years we sat on the same father’s lap, you on one knee, me on the other. You can’t actually rub that out just like that. Just look at us now, old and naked beneath our bathrobes, in our plastic slippers. Old and a bit wiser, I hope. Let’s not accuse one another, but celebrate our reunion. I suggest we get dressed and go to a pâtisserie in the street named after Queen Astrid. They have …’ she kissed her fingertips, ‘delicious cakes there.’

Lotte’s rage ebbed away. She nodded, ashamed that she had let go like that. Together they walked along the imposing passage to the lockers. Together – what a word.

A quarter of an hour later they descended the steps of the monumental bathhouse, involuntarily holding on to each other because it was snowing and the steps were slippery.

It was not far. They went inside a nondescript shop, walked through to the back, past a display cabinet of delicacies gratifying to the eyes, to a refurbished living-room where elderly ladies in fur hats were succumbing in complete silence to the matriarchal rite of coffee and cakes. A wagon wheel lamp fitting hung from the ceiling and cast flattering light onto the clientèle; on the walls paintings of imaginary landscapes in gaudy colours confirmed the atmosphere of reassuring kitsch.

They ordered ‘merveilleux’, an artful variant on a mouthful of air, held together with meringue, whipped cream and flaked almonds.

‘Now I understand whom I heard singing yesterday.’ The piece of meringue that Lotte was bringing to her mouth came to a pensive standstill midway.

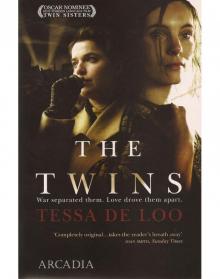

The Twins

The Twins