- Home

- Tessa de Loo

The Twins Page 17

The Twins Read online

Page 17

With a teasing expression on her face she sang softly:

‘Ding ding ding

comes the tram

with the conductor

and if you don’t have fifteen pence

you have to run behind it …’

Nothing in the children’s song, which could have been the key to their mutual recognition, the renewal of the old bond, had aroused anything in Lotte – perhaps too many arias and cantatas had slipped in between. Anna looked at her expectantly. Lotte replied to the test of authenticity with an embarrassed shrug of the shoulders. Silently Anna turned away from her and transferred her attention to the dark grey surface of the Rhine. The tram rumbled over the bridge. It seems as though she rather reproaches me, thought Lotte, perhaps she has seen me as a deserter for eighteen years.

‘Eighteen years …’ she now said aloud, ‘it’s eighteen years ago …’ Suddenly the spell seemed to be broken. The tram reached the other side. ‘Why did you never write to me … at the time?’ Lotte asked, like a tentative defence and attack combined. ‘Because I heard nothing from you,’ Anna snapped. ‘That can’t be so,’ Lotte lashed out, ‘I wrote dozens of letters to you and each letter ended with: Anna, why don’t you write back?’ Anna seemed disturbed from her composure just for a moment. But it was no more than a ripple – she shrugged her shoulders and said flatly: ‘Then they intercepted those letters. I never received them.’ Lotte looked at her with bewilderment. ‘Why would they do a thing like that?’ Anna stared outside ostentatiously, as though it did not concern her. ‘You don’t know them,’ she said disinterestedly. Disconcerted by excitement and indignation at Anna’s detachment – this was a crucial point – Lotte cried: ‘They couldn’t do that, just like that?’ Impassive, Anna turned her face to her: ‘That’s how they are.’ Irritably she added, ‘It’s best to get the bad things said straight away … You have come here full of expectations but I … I’m telling you honestly … I really do not know what that is … family … or a special family feeling. I’m sorry, but now that you’ve suddenly returned like a female Lazarus I don’t know what to do with you … Long ago I had already reconciled myself to my fate of being alone on this earth … I belong to no one, no one belongs to me, those are the facts … I have nothing to offer you …’

‘But yet we’re … we have the same parents …’ Lotte repudiated weakly, ‘that must count for something surely? In order to know who we are we must surely know … how it all began …?’ ‘I know precisely who I am: nobody. That suits me very well!’ Bitterness shimmered through her provocative position, making her voice loud and rough. Some passengers looked round. Lotte remained silent, intimidated, she was in a cold sweat. Again she had the feeling that Anna was blaming her. But for what? For still being alive? For wanting to give the term ‘sister’ meaning? Was this her punishment for the long-cherished illusion of two orphans who would finally plunge into each other’s arms, pure and unsullied by time, distance and family matters? Grandmother’s description of the small-minded Catholic milieu of primitive farmers was now really taking shape.

Later she would reproach herself that she had not decided at that moment to come straight back on the same tram. There was no more doubt that the reunion was a disillusion and that the stay could only make everything worse. It would still be possible to spend New Year’s Eve at home, with mulled wine, lardy cake and music. But a misplaced sort of stubbornness compelled her not to be daunted. In the German fairy-tales that she had been over-fed on as a child, many-headed monsters and dragons had to be slain to free the magic princess. Perhaps she was refusing to admit the failure already at this stage, perhaps she wanted to put off the moment when she would return home without illusions, perhaps she hoped to break through the armour and learn about what was still hiding beneath it.

The tram stopped. Anna indicated that they had to get off. This was her last chance: I’m sorry, Anna, I believe it would be better if I went back – but she stood up and snatched her suitcase; all of a sudden she could not bear the thought of Anna appropriating it again. They got off, it had become dark, and icy cold, the suitcase knocked against her leg with every step. ‘All cars have been requisitioned,’ Anna explained coolly. ‘Now we do everything on foot.’ Iron gates opened, a drive lined with dark tree trunks stretched out before them, the moon performed a sinister shadow play with the branches above her head. We are going the same way for the first time, she and I, thought Lotte, and a misplaced sentimental feeling flowed through her. She still had the inclination to embrace her sister, who walked next to her in fierce silence … let’s give up this charade for God’s sake. But they walked along the endless drive a metre apart from one another, together and yet separate. A white house fluoresced in the dark, with blind, black windows. Wide stairs describing an elegant arc, first curving away from each other and then coming together, led to a baroque entrance.

Preparations for New Year’s Eve were under way within the darkened house. Herr von Garlitz was expected home; his wife was trying to estimate how much food and drink his companions would get through. Helped by her status, money and charm, she knew how to get hold of a variety of products that had been unobtainable for ordinary people for a long time. Anna displayed feverish industry from Lotte’s arrival to her departure. In between the activities she introduced her sister to the Countess, the cook, the butler, the governess and the other members of the staff, all exactly as was proper but without any kind of enthusiasm. The two sisters were compared. You could see it in the eyes, pronounced the cook, the same blue, but beyond that the differences were greater than the similarities. Frau von Garlitz complimented Lotte on her German. Eighteen years and still quite without accent! The work was hectic. You could already smell New Year’s Eve in the kitchen, its arrival was tangible in the staff’s tense activity. Lotte stood at the window of her guest room in pyjamas and looked out through a chink in the black-out at the reflection of the moon in the swimming pool. Anna had said a curt ‘gute Nacht’ and not exchanged another word with her. The day ended in greater mystery than it had begun. Instead of ‘How will Anna be?’ it was ‘Who is Anna?’

The following day was also about staff busily walking back and forth, involved in dim preparations, until an invasion of officers forced them back to the wings. Lotte fled into the grounds. If at first she had only felt unwelcome, the uniforms and caps, loud voices – some with drawling eastern sounds or an ugly rolled ‘r’ – made her into a confirmed outsider. Shivering, she walked in the park. German ground. German grass. German trees … Country of her birth? The kitchen garden at home and the neglected fruit-trees struck her as a paradise compared with this emphatic wealth per linear metre of lawn, per square metre of swimming pool, per cubic metre of German air. The rest of the day she wasted in the staff sitting-room, leafing through the Illustrierte Beobachter, already contemplating the return journey and the way she would disguise the disillusion at home. The evening meal in the kitchen was bolted hurriedly; Anna appeared at table in a black dress with a white, starched collar and a cap on her head. ‘Here you see what a chambermaid’s life is like,’ she said, again managing to make it sound like an accusation. ‘Can I help anywhere?’ Lotte stammered. ‘Why not?’ said Anna sarcastically. ‘I have another uniform like this, that will be a splendid metamorphosis.’

Lotte let the waitress’s dress slide over her shoulders – a desperate attempt to creep into Anna’s skin, or at any rate to be twins on the outside for once. She entered the dining-room with a soup tureen in her hands, her gaze straight ahead on the bow of Anna’s apron ribbons, which had been tied with mathematical precision. The officers, who had exchanged their uniforms for dinner-jackets, were seated on either side of a long table decorated with evergreen sprigs. Candles in branching candelabras glittered in the table silver and in the dark red sequins on the Countess’s low-cut dress. She sat at the head of the table, twinkling; her husband sat opposite her in his dual role as host and officer. Anna and Lotte were unnoticed as they put the

dishes down – as though they were transparent. Anna’s phrase ‘I am nobody’ acquired an additional dimension. They went back noiselessly; serving was the waiters’ job.

That is how the festive evening slipped through their fingers in dull servility. Dirty plates, glasses, spoons, empty dishes. The guests became increasingly boisterous, it was hard to keep up with the pace at which wine and Sekt had to be fetched. One of them, a well-fed officer with a shining red face, performed an improvised sword dance with one of the weapons taken off the wall, around his half-empty glass which had been uprooted and placed on the parquet floor. Anna’s arrival with a strawberry bavarois disturbed the acrobat’s concentration – losing his unsteady equilibrium he thudded backwards onto the solitary piece of family crystal. With bloodshot eyes he crawled back onto his feet, the fragments sticking out of his backside like crows’ feet. Enthusiastic applause rang out. One guest roared, ‘The first victim has fallen at the Westwall!’

At that moment Lotte, also carrying a dish of bavarois in her hands, became convinced of her sister’s fearlessness. Anna set the dish of gently wobbling pudding on the table, bent over the affected area and picked among the pieces there with a neutral expression, as though she were gleaning corn. Then she supported the wounded one towards the bandage cupboard. Just before leaving the room, he laid his hand on her bottom, to indicate that his spirit was unbroken – Anna coolly pushed the hand away.

Around midnight the staff crowded together in the communal sitting-room and at twelve they hugged each other with foaming glasses in hand. The sisters kissed each other like ice queens. Something external immediately provided them with a magnificent excuse to distance themselves again: a rifle shot, and then another, made everyone rush over to the windows. Lights out, someone roared. They rolled up the black-out curtains and pressed their noses to the glass. ‘Dear heaven,’ groaned the cook, ‘they’ve gone mad!’ Some officers, laughing and hawking, were aiming at a white bath towel hanging over a low branch. They shot again, the material moved a little and fell back slack. The cook went to the door. ‘It’s a scandal,’ she cried angrily, ‘I’m going to do something about it!’ The governess stopped her: ‘Calm down, Frau Lenzmeyer, it’s not up to you to call senior officers to order.’ The cook knocked back a few glasses of Sekt in frustration. The shooting continued. Lotte slipped out to her room unseen, where she let herself drop onto the guest bed.

The shots in the night and the image of the riddled towel brought to mind the disquieting stories of Theo de Zwaan and Ernst Goudriaan on their return from Germany – stories that had only increased her longing. It was only now that they took on meaning: she felt the threat that emanated from each shot, fired out of boredom and the lack of a more suitable target. Up to now ‘enemy’ had been an empty word – here it was acquiring significance. A significance that replenished itself with Anna’s cold New Year’s kiss, with a gloomy walk in the grounds, with the failure to retrieve anything as vague as country of birth. The shooting stopped, a song started up instead. In utter loathing she screwed her eyes shut. She took the cap off her head, untied the apron and looked at herself in the mirror. The black dress exactly suited the funeral of her illusions.

She had already put her suitcase in the hall when she went into the kitchen for breakfast. It looked as though they had worked the whole night through – not a dirty glass or scrap of pudding recalled the previous evening. Everything was focused on a hearty breakfast; on no account could the guests return to the Westwall on half-empty stomachs. Anna hurried to and fro, composed, without a trace of weariness, her blonde hair correctly waved around her cap. Lotte approached her about the tram departure times. She would enquire, she called over her shoulder, disappearing down the passage with a silver dish full of rolls. Ignoring Lotte’s objections, Frau von Garlitz decided that one of the officers would take her to the station.

The guests automatically allowed Anna to help them into their heavy coats, embroiled in their conversations right up to leaving. Lotte stood by stiffly, holding her suitcase. The acrobat grumbled noisily to his neighbour about the tenants on his property in Brandenburg. ‘They are so stupid, so dirty, indolent – actually they’re not people, but somewhere between person and animal …’ Anna froze, his coat in her hands. ‘It is easy for you to talk,’ she said sullenly, ‘I’d like to see you if you had to drudge like a farmer.’ All heads turned towards her; the Countess looked on open-mouthed. In pure astonishment at such impudence, the officer permitted her to help him into his coat as willingly as a baby. His face went the same colour as the previous evening after his fall; it was probably the recollection of her efficient management of him that restrained him from demanding her immediate dismissal. At that moment the signal for departure sounded on the other side of the vestibule. Lotte grasped her suitcase. Anna came up to her to shake hands. She smiled again for the first time since Lotte’s arrival – perhaps less from friendliness than out of satisfaction at the way she had cut an arrogant landowner down to size. ‘We’ll write sometime …’ she said looking over her shoulder – Frau von Garlitz was calling her. The last thing Lotte heard was her cultured, enraged voice: ‘Who do you think you are, offending our guests! If I ever see anything like that again …’ A short, stocky officer seized Lotte’s suitcase and hurriedly pushed her outside. She climbed into a military car. She let herself be driven away without turning round, down the drive, into a suburb swathed in profound quiet. Anna kept reappearing with raised chin, a coat in her hands, and each time she heard her angry retort, which had to be a justification for her own past. The designation ‘barbarians’ resonated in a remote corner of Lotte’s mind. Curiosity overcame her: Anna’s unflinching honesty had admirable aspects. But it was too late, they were crossing the Rhine – inaccessibility through distance would be less chafing than inaccessibility in proximity. She stared at the Cathedral. The two towers propelled upwards – already centuries ago they must have found a method for remaining joyful beside each other at their point of origin.

Throughout the journey the officers were silent to the parcel from Holland that had to be delivered to the station.

2

In a gust of cold air a boy came in, followed by his father who had bought one of the helmets at the market. He put it on his son’s head, grinning, after he had ordered two Cokes. Even from the table where Lotte and Anna were sitting it was evident that the father–son romance was revived by the purchase of the helmet. As long as the glow lasted they were participants in the same adventure, a war in which neither of them had been involved. If there had been a feather headdress in the market, then the battle of Winnetou against the whites would have easily had the same effect.

‘American Coke and a German helmet …’ Anna shook her head, ‘I’m getting old.’

Lotte’s thoughts had not disengaged from that unfortunate New Year’s Eve. ‘I’ll never forget it,’ she murmured, ‘all those drunken, shooting officers … I had the feeling I was among fanatic Hitler-supporters.’

‘Are you mad?’ Anna sat up straight; something needed putting right. ‘The von Garlitz family, they were old nobility, they were industrialists! Of course they had helped that buffoon into the saddle; in return he polished off the communists and got them their Greater German Reich. But you don’t really think they thought much of the son of a customs official? They were able to use him well, for a while; only when it was their turn to die on the battlefield did they realize that that parvenu had used them too.’

She burst out laughing.

‘What is there to laugh about?’ said Lotte tetchily.

‘I can still see myself running through that house in cap and apron. What a misery. All the time I was trying frenetically to forget that the visit was for me – think about it, for the first time in my life I was being visited. You have no idea what difficulty it caused me. Those officers were a lovely alibi. How I worked!’

Lotte was silently building a pyramid of sugar lumps. ‘It has stayed with me like a decadent image,’

she murmured, ‘those officers in the night … an enemy you can expect anything from if he is capable of shooting at towels …’

‘They were dancing on top of a volcano,’ Anna interrupted her. ‘Why do you think they drank so much?’

Anna paced about in her bedroom. Her body hurt with every step, as though someone had given her a beating. She struck her fist into her palm. The recurring silence was unbearable. It was a silence with a double foundation, left behind by someone who had now gone away for good. Not because others had arranged it so, but through her own guilt. She was besieged by images she had seen fleetingly in between work duties: her sister’s figure – in the grounds with coat flapping about, alone at the long kitchen table by an empty plate after the meal, seen from behind as she went upstairs despondently. Piece by piece, silent indictments. Rewinding and playing the film again – differently. Too late, too late, too late. Why, that was what she wanted to know. The answer would not be found in the best-equipped library but was hidden in herself. The only thing she knew was that, from the moment Lotte had turned to her on the platform, she had come face to face with her father. His long curved nose, his narrow face and dark wavy hair, his melancholy, stubborn gaze. There was something improper – as though Lotte had robbed him or caused unfair competition. In Lotte she did not encounter the thickly swathed six-year-old sister who had been abducted by a woman in a veil. Now there was someone else who could exert rights over her father, someone who was perhaps more entitled than herself because she looked so staggeringly like him. So this was Lotte. Why now?

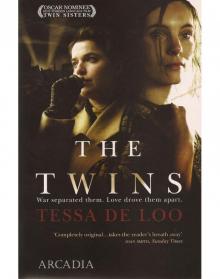

The Twins

The Twins